Analysis: The Impact and Future of the Met Museum API

by Alyse Delaney, December 2022

In today’s hyper-connected digital sphere, a website unlinked to the wider web has metaphorical walls much like the physical gallery space. Information may be buried deep within pages or databases and require substantial digging on behalf of the visitor to find the information they want. The largest impact of the Met’s Open Access program is in the reach their collection now has beyond the museum’s website. The API has been utilized by students to create visualizations revealing insights about the collection makeup and by computer scientists developing artificial intelligence systems to automatically tag works of art with relevant keywords. Through third-party applications the public is now able to more easily search and explore the Met’s collection. These applications can function as educational tools, meant to teach viewers about art historical periods; as inspirational tools, meant to illuminate creative connections between works in the collection; and as calls for action, meant to reveal shortcomings and potentials in the development of the museum’s collection.

Linking Data to the Outside World

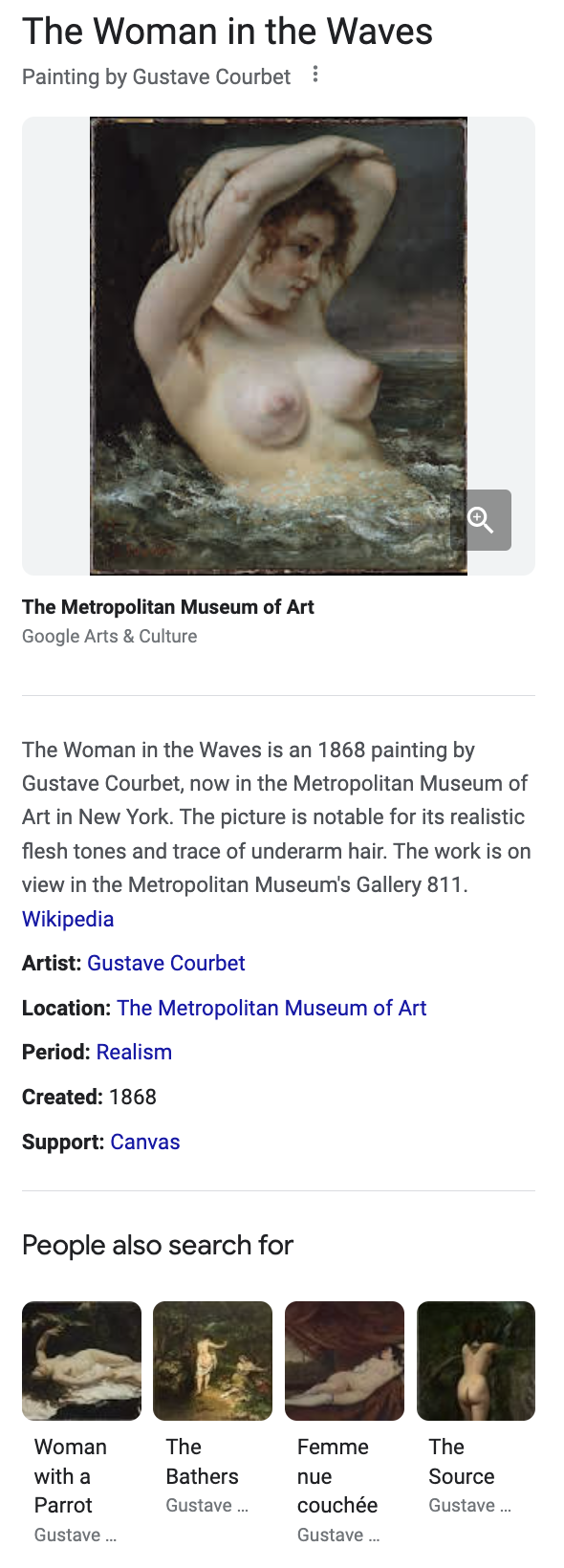

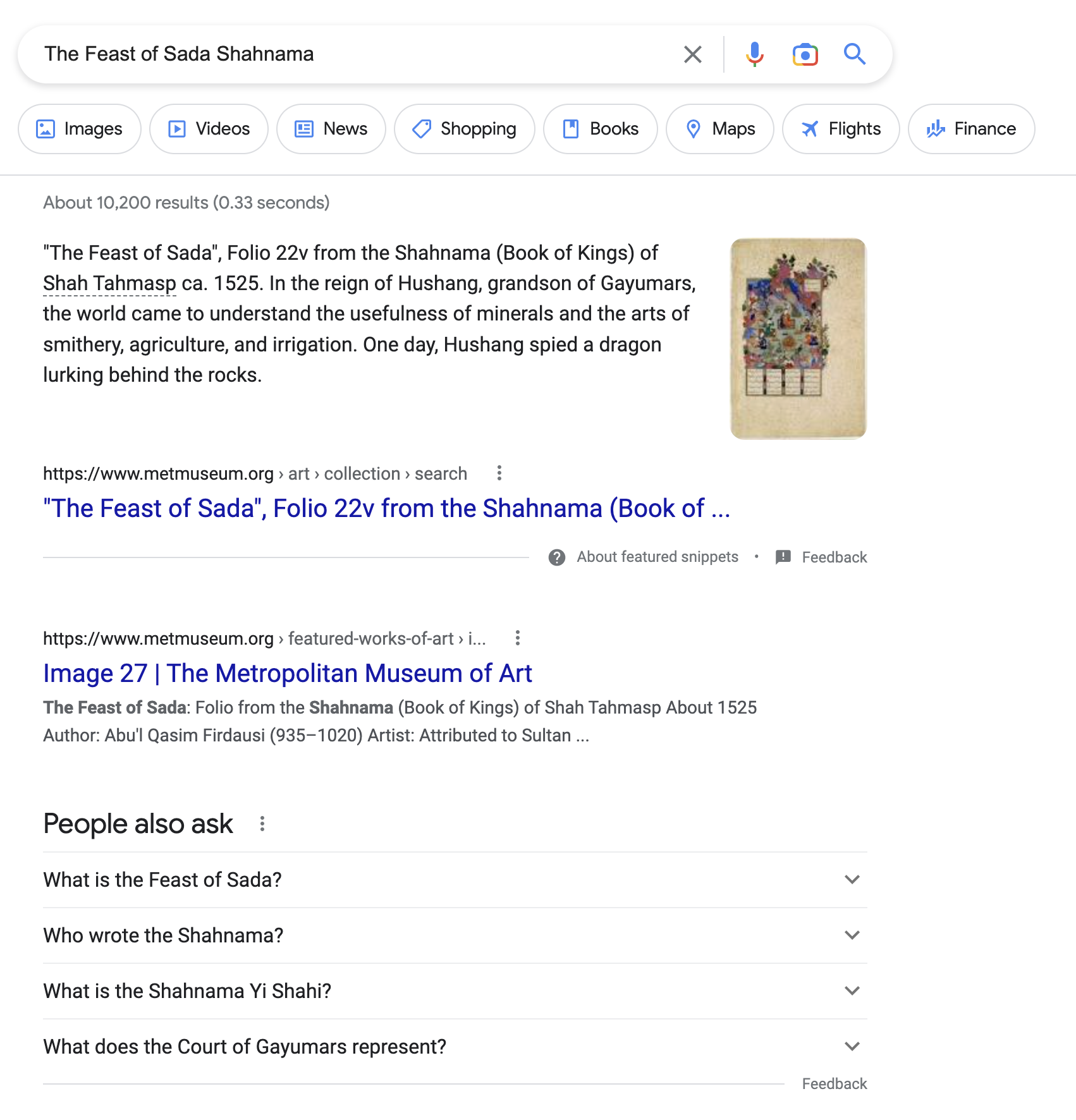

When the program launched, the Met formed partnerships with institutions like Google, Wikimedia, Artstor, and the Digital Public Library of America. Each of these partnerships extend the collection into the world wide web. The Met’s primary partnership with Google is in its contribution to the Google Arts & Culture project. Once the API was developed, the museum was able to automatically deposit 200,000+ works of art into the cross-institutional repository. Previously, the museum staff had to enter the records by hand and had only completed 757 records.* Partnering with Google also means that the metadata about works of art is searchable via the Google Knowledge Graph, which forms the at-a-glance summary box frequently displayed at the top of a page when you perform a Google search. Now, if a user searches for “Courbet Woman in the Waves” they can get immediate information about the painting, with links to Wikipedia, the Met, and related artworks in other museums’ collections. Unfortunately, this tool seems to work mostly for prominent Western artists and works of art. A search for “The Feast of Sada”, a folio from the notable manuscript, Shahnama (Book of Kings), which is marked as a highlight of the Islamic Art collection, provides a brief summary but no such blurb on Google despite an extensive Wikidata entry on the work.

*Scaling the Mission, Tallon

Left (Figure 3): Screenshot of the Google search results for "Courbet Woman in the Waves".

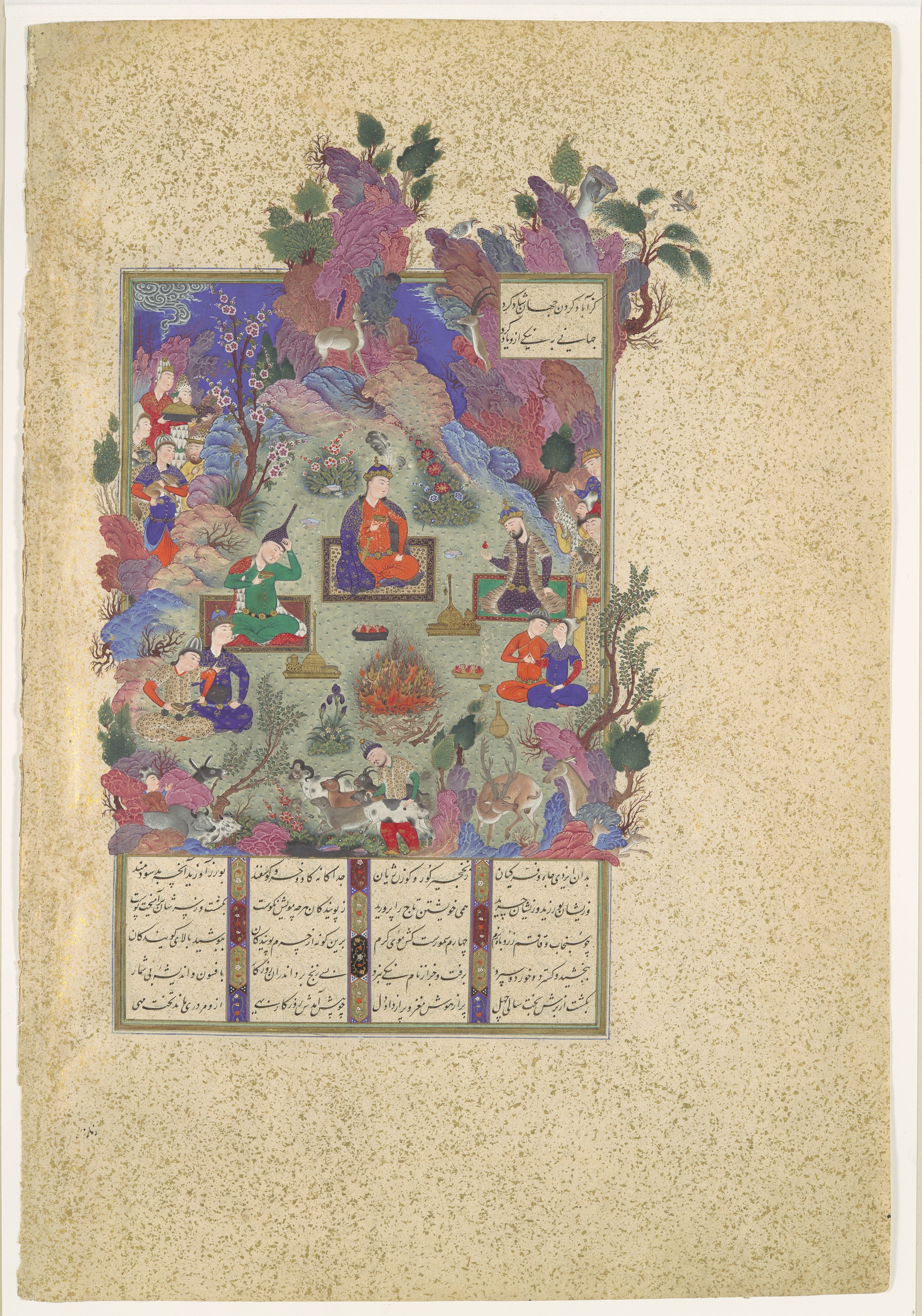

Middle (Figure 4): "The Feast of Sada", Folio 22v from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, ca. 1525, view at metmuseum.org

Right (Figure 5): Screenshot of Google search results for "The Feast of Sada Shahnama"

Google’s Knowledge Graph is one instance of the growing trend to connect information online via linked open data, and it is a movement picking up in cultural institutions to connect their resources to others’. By uploading their data into Wikimedia (the underlying repository of Wikipedia), the Met has contributed knowledge about their collection into the global knowledge base.* Its data is now semantically connected to other pieces of data on the web. These links can be identified in the metadata records provided by the API. For instance, in the record for Courbet’s Woman in the Waves, the artist’s identifier in the Getty Union List of Artist Names is included:

*via Creating Access beyond metmuseum.org: The Met Collection on Wikipedia Loic Tallon

"constituents": [

{

"constituentID": 161790,

"role": "Artist",

"name": "Gustave Courbet",

"constituentULAN_URL": "http://vocab.getty.edu/page/ulan/500010927",

"constituentWikidata_URL": "https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q34618",

"gender": ""

}

],

And is tagged with the (somewhat disappointing and reductive…) keyword, “Female Nudes,” pulled from the Art & Architecture Thesaurus:

"tags": [

{

"term": "Female Nudes",

"AAT_URL": "http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300189568",

"Wikidata_URL": "https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q40446"

}

],

And the artwork as a whole also has a Wikidata tag:

"objectWikidata_URL": "https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q39013",

These links to controlled vocabularies and Wikidata URLs essentially make sure every institution is talking about the same instance of an artist, subject, medium, etc.. In turn, linking the item to these instances allows it to be connected to larger ideas and related concepts. For instance, the Met’s website may not explicitly say what movement Courbet belonged to (Realism) but the Wikidata URL ultimately situates the artwork within a networked field of knowledge and provides links to further explore the topic via Wikipedia. This has tremendous reach in terms of bringing the collection as an educational tool to the wider public, as most search engines use Wikipedia and its underlying databases as the first point of access when fulfilling queries. Museum staff observe that users will have a deeper engagement with the works via the museum’s website, but the existence of the data via Wikipedia provides crucial access points to the information.*

*Scaling the Mission, Tallon

Next Steps: A Call for Intuitive, Inclusive Searching

Overall, while the API is an amazing tool developed by the Metropolitan Museum of Art to expand the reach of its collection, there is still much room for development in providing visitors with quality engagement in terms of information retrieval. Most notably, this could be done through improvement of the search tool in the digital collection.

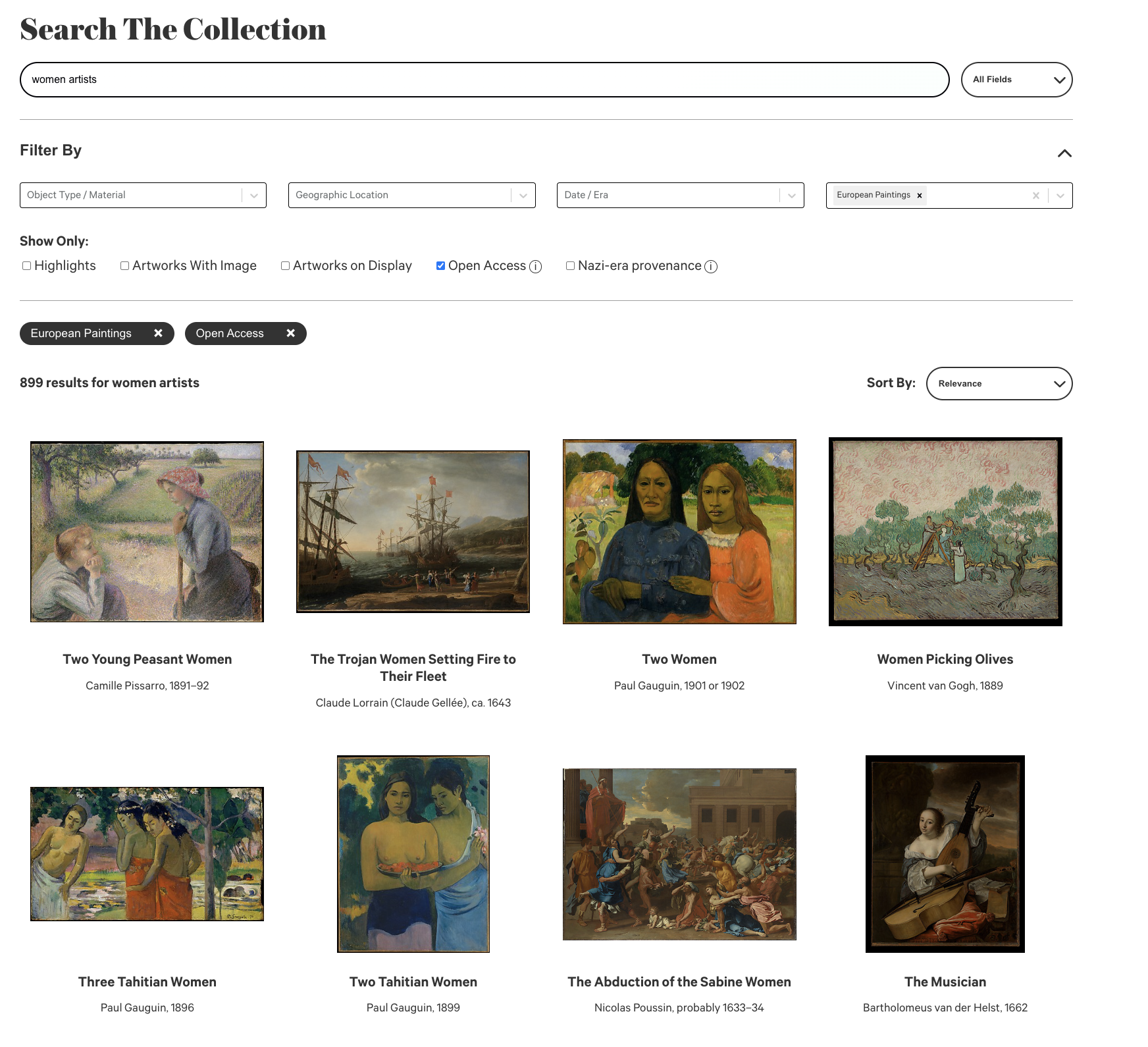

When browsing without a particular search in mind, the current filters are difficult to understand for anyone not familiar with art historical language or the collection’s design. Under “Object Type / Material” what is the difference between “Albumen” and “Albumen silver prints”? If a user is trying to identify African art objects, how will they know that these objects actually actually, suscipiciously belong to the “The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing” without any further indication? Furthermore, keyword searches frequently fail to provide accurate results. Why, for instance, when searching for “women artists” in the department of European Paintings, are only 8 of the 40 artworks displayed on the first page of results actually painted by women? Is this a shortcoming of the collection itself, or a shortcoming to adequately convey the scope of the collection to their users?

(Figure 6) Screenshot of the search "women artists" performed in the Met's Digital Collection

While curious visitors may now be able to answer many of these questions through Google and the broader internet, the museum’s website should still provide comprehensive access for those looking to dive deeper into the content. Unfortunately, intuitive searching typically depends on keywords linked to artworks manually by museum staff. There have been initiatives by the Met to crowdsource tagging, and, as previously mentioned, computer scientists are currently using the API to train software to automatically classify artworks.* Hopefully, this will expedite the process and relieve the labor intensive work of human catalogers. Possibly, a simpler adjustment could be made by narrowing down the filters, or by providing broader categories. Perhaps it would be more intuitive to have a filter for artwork form (Painting, Sculpture, Drawing), and then narrow down into materials. This information is easily connected to the digital collection via the API. For instance, the museum is currently working to include gender information about artists in the metadata, which in turn should ideally populate the search for “women artists.” Ultimately, utilizing linked data and semantic language has the potential to make searching more intuitive for the average, everyday visitor. Hopefully, the API will provide the museum with the ability to analyze its own shortcomings and provide greater discovery and exploration opportunities for its visitors.

*via Engaging the Data Science Community with Met Open Access API, Jennie Choi

← Previous: Accessing the Data